by Buck Institute

January 15, 2020 . BLOG

Ow-steoporosis: New research directions for a common condition

By Garbo Gan, Former Lab Technician in Kennedy Lab

By Garbo Gan, Former Lab Technician in Kennedy Lab

On a warm Saturday morning, my 83-year-old great-aunt Margaret* was strolling through the park. While descending a small flight of concrete steps, she lost her footing and found herself at the base of the stairs. To her surprise, she was unable to get up. Her left leg felt numb and unwieldy, like a limp carrot.

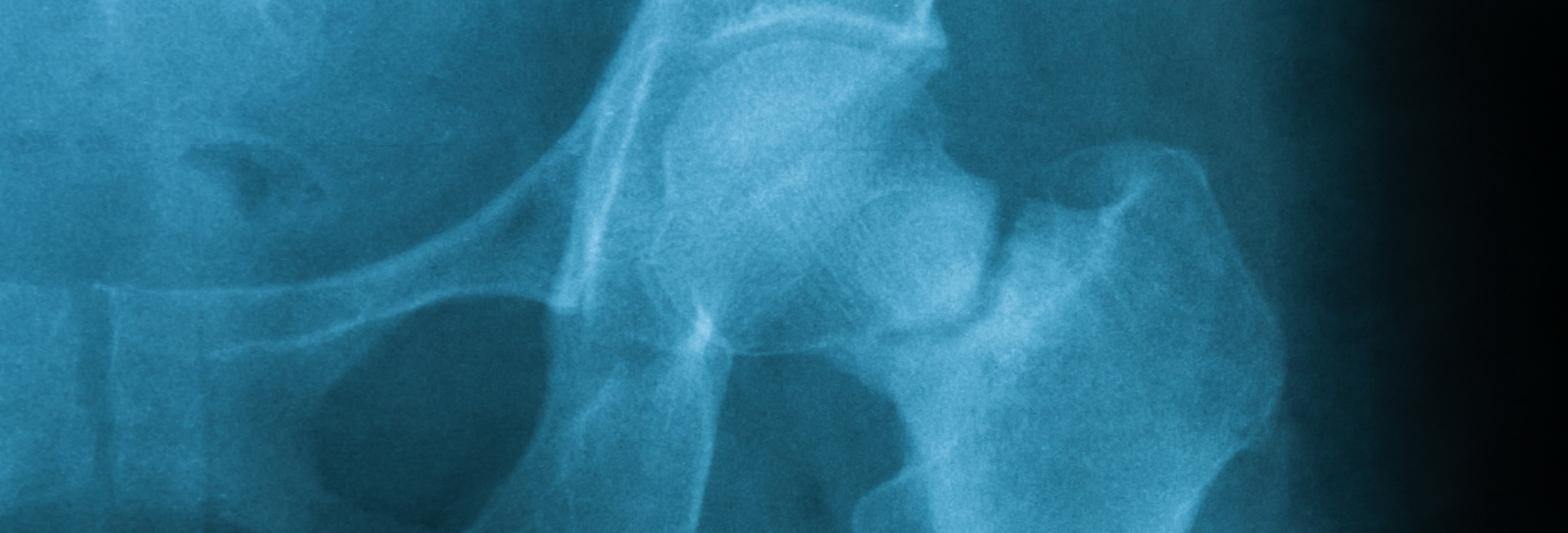

24 hours later, Margaret was wheeled into surgery. A radiology technician had taken an x-ray of her left hip. On the long bone of the thigh (femur), right below the ball that sits in the socket of the hip, was a fracture line. Margaret had broken her hip during the fall and needed a hip replacement as soon as possible.

Margaret was diagnosed with osteoporosis, a health condition in which bones become brittle and porous, making them more likely to fracture when a strong force is applied. It is incredibly common, but not yet well understood. Osteoporosis develops so slowly over the years that it is often undiagnosed until a fracture occurs, as was the case with my great-aunt. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation, “One in two women and up to one in four men will break a bone in their lifetime due to osteoporosis. For women, the incidence is greater than that of heart attack, stroke and breast cancer combined.” Since women have lower peak bone mass than men, and also undergo hormonal changes in menopause that can further exacerbate the decrease in bone density, women are more likely to experience fractures resulting from osteoporosis.

X-ray image of femoral neck fracture, AP view, showing femoral neck fracture.

Xray scan of patient who have hip replacement and knee arthroplasty (knee replacement) treatment for Osteoarthritis knee, hip arthritis, Osteonecrosis of Hip. After surgery patient can walk normally

Breaking a bone- and recovering from a fracture - can be a painful and troublesome experience, especially if it reduces a person’s mobility. For older adults, broken bones are associated with an increased risk of dying within the following 10 years. For hip fractures, this excess risk is highest in the year after the injury. 33% of men and 20% of women die within a year after a hip fracture. While it is not clear how the association between broken bones and an increased risk of death can be explained, it is possible that the health declines that had led up to the fracture may play a part. For that reason, it is quite worthwhile to invest in the management and prevention of conditions that put one at greater risk for osteoporosis.

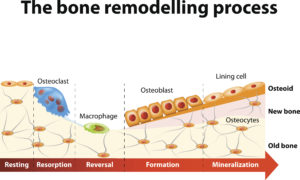

The bone remodeling process involves the following steps

Bone remodeling is the two-part process of breaking down and rebuilding bone matter. When we are young, bone building occurs at a higher rate than break-down, and thus bone remodeling leads to an overall increase in bone mass until about age 30. Afterwards, a slow but steady net loss of bone mass begins. When women reach menopause, their rate of bone loss temporarily accelerates even more because of the decline in circulating estrogen. There are still many unknowns about the connections between estrogen and bone health.

In January 2019, a team of scientists from UCSF and UCLA published a novel discovery about a brain-to-bone connection: blocking estrogen receptors in a specific region of the female mouse brain led to a 7-times increase in bone density. After genetically removing the estrogen receptors from this region of the brain, the researchers observed that the female mice were able to grow exceptionally strong bones that retained their density well into old age.

Scientists were curious about how this finding might relate to hormonal changes during menopause. To investigate this, they conducted experiments to determine what would happen if this brain-to-bone pathway were blocked in a menopause mouse model. During menopause, ovaries produce less estrogen. Since mice do not undergo menopause, scientists perform an ovariectomy (surgery to remove ovaries) on the mice to mimic the female human body’s biological environment of decreased estrogen after menopause sets in.

Ovariectomized (OVX) mice, upon deletion of estrogen receptors in the same region of the brain, not only had greater bone density than OVX mice without removal of estrogen receptors; they also experienced an increase in bone mass, suggesting that the brain’s pathway may play an important role in ameliorating decreases in bone density, perhaps to a greater extent than circulating estrogen.

What does this mean for the future of osteoporosis research? First and foremost, the results should not be inferred as medical advice, as there is no guarantee that what works for mice will also work for humans. However, they are an indication that scientists may be close to targeting a previously-unknown pathway of bone growth to develop new therapies for bone loss. Although researchers have generally agreed that circulating estrogen in the blood is important for the maintenance of bone density, this study has shown that estrogen acting in the brain may contribute to the loss of bone density. We still have a lot to learn about the effects of this hormone, but the discovery paves the way for more questions about the possible methods of treatment of bone diseases, and we cannot wait to find out more.

*Names and other personally identifiable information have been changed to protect privacy. Any resemblance to real persons is unintentional and coincidental.

SHARE