by Buck Institute

October 19, 2023 . BLOG

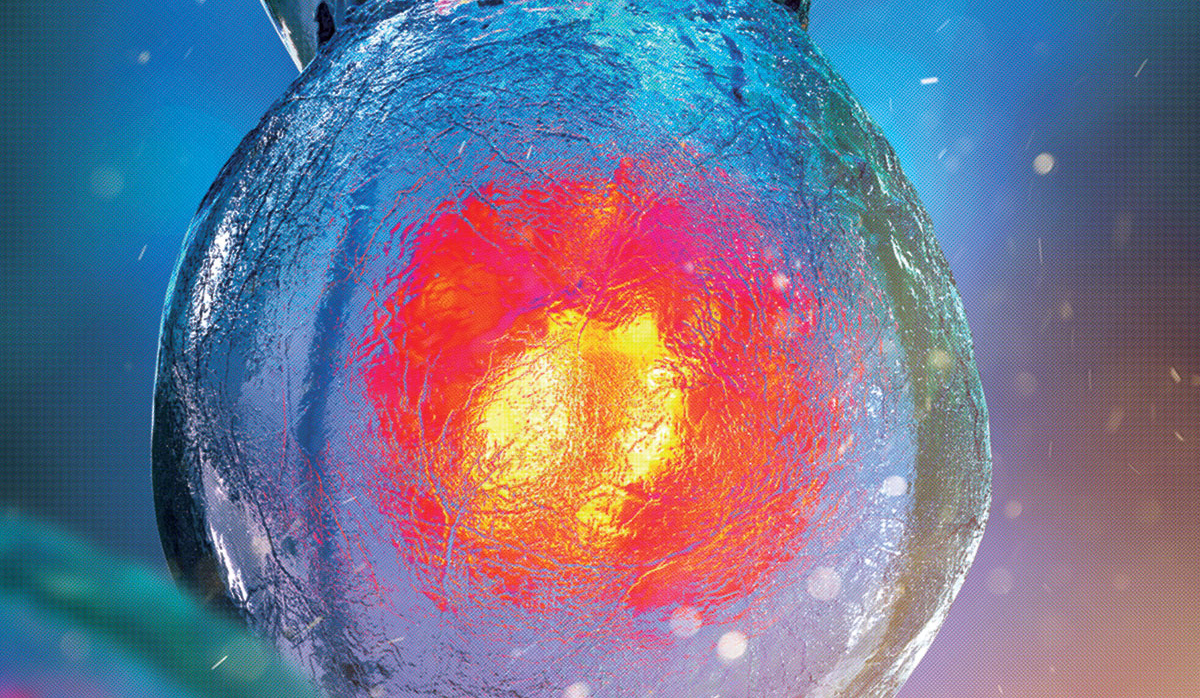

Looking to Mitochondria for Insight about Fertility and Aging

Buck postdoctoral fellow receives grant from the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity & Equality

Mitochondria are famous for being the powerhouses of the cell, supplying most of the chemical energy needed to fuel biochemical reactions. But they are so much more than that, says Olga Bielska, PhD, who became enamored of mitochondria during her graduate studies in France.

Mitochondria are famous for being the powerhouses of the cell, supplying most of the chemical energy needed to fuel biochemical reactions. But they are so much more than that, says Olga Bielska, PhD, who became enamored of mitochondria during her graduate studies in France.

“They beautifully orchestrate so many functions beyond just energy production, and may hold the key to understanding aging.” says Bielska, who is a postdoctoral scholar in the lab of Buck President and Chief Executive Officer Eric Verdin, MD.

Bielska recently won a two-year $200,000 award to use the mighty mitochondria to explore a gene that regulates mitochondrial division, with the goal of linking aging, mitochondria, and infertility. The funding came from the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity & Equality (GCRLE) at the Buck, made possible by the Bia-Echo Foundation. The GCRLE is dedicated to supporting breakthrough research on reproductive aging.

Bielska is studying a mitochondrial division protein, which she and her labmates noticed decreased in multiple organs as mice age. They also noticed that these mice had fertility problems; they were unable to conceive or produce any progeny, which led her to propose her current study linking the pathway of mitochondrial division to infertility.

What is currently known in the field of reproductive biology is mostly damage to the DNA in the nucleus of the cell, says Bielska. “What we have discovered is a nuclear gene that regulates mitochondrial health. It is completely novel and not explored yet.”

Bielska applied for and won a GCRCLE award to better understand how the loss of this protein affects fertility in mice. The work will provide insight into the processes in women, as humans have an equivalent genetic pathway in our own mitochondria.

Damage to nuclear DNA affects female reproductive health. For example, women who have some mutations in genes that regulate the DNA damage response may have premature menopause or have fertility problems. Even before menopause, women are less able to conceive as they get older.

“However, there is not much known about the role mitochondria may be playing in this decline,” Bielska says. “We hope that understanding this molecular pathway may give us some clues about how to better design potential therapies to extend fertility in women.”

Beyond fertility, the work has implications for understanding the aging process.

“The changes we observe are not taking place only in the reproductive system, we see the same in other organs,” she says. “They appear to be very much age-related.”

In general, aging occurs as mitochondrial function declines. “We know that mitochondria are not functioning well in aging, but the question is: why is this happening? We don’t really know what causes this dysfunction,” says Bielska.

The research may uncover new insight into mitochondrial aging. Since Bielska’s team thinks the regulation of mitochondrial division is important for natural aging, she says their goal is to understand it so that they can design better therapeutics to prevent its loss or reactivate it in aging organs.

“We discovered a target for age-related mitochondrial dysfunction,” she says. “It is a completely new story.” This new chapter in understanding how mitochondria work has “huge potential for the future of fertility studies and longevity therapy in general,” she says.

SHARE