by Buck Institute

May 5, 2021 . BLOG

Healthcare Around the World: Costs, Covid, and Comparisons

This is the 5th blog in our series from MS Biology students from Dominican University. In this post, student authors Sergelen Ariunbaatar, Enrique Carrera, Angelina Malagodi, and Buay Deng dive into the fundamentals of different healthcare systems and how they responded to COVID-19 globally . You can catch up on the series by reading the first blog, about vaccines, the 2nd about prevention, the third, about the history of pandemics, and the 4th, about vaccine science.

By: Sergelen Ariunbaatar, Enrique Carrera, Angelina Malagodi, and Buay Deng

Edited by Professor, Dr. Pankaj Kapahi

Do you feel your health concerns have increased during the covid pandemic? Now multiply this by the nearly 8 billion people worldwide who have spent the past year worried about their health. We, a group of masters students in health sciences, also share this concern and wanted to delve a little bit deeper. Our first question was about how Covid-19 impacted healthcare systems. We quickly realized that we need to understand what healthcare systems really entail before addressing this question. After describing the major worldwide healthcare systems, we’ll dive into how COVID impacted them, and follow up on how healthcare and money are influencing current vaccine distribution efforts.

Simplification of healthcare types

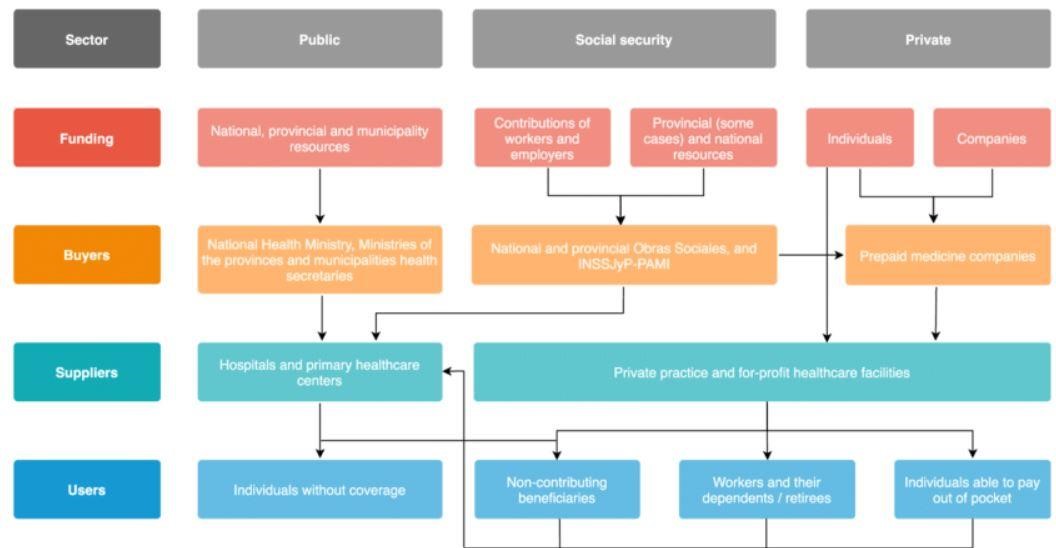

The vastness of the topics covered under healthcare can be overwhelming. As seen in the diagram above from Palacios et al’s breakdown from Argentina’s healthcare system, it can become non-linear quickly. The intersectionality of healthcare definitions also muddle defining each nation's healthcare system. For example, within the United States there are healthcare models that include both non-universal and private healthcare.

Based on some dominant themes in a Commonwealth Fund report, we developed our greatly simplified table below.

|

Healthcare type |

Description |

Benefits |

Pitfalls |

Example countries |

|

A sole payer is responsible for covering all health insurance. The funds are typically supplied by taxes. |

Eliminates medical cost burdens and ensures standard quality of care. |

Limited funding can cause restrictions on the type of services provided.

Citizens often purchase their own supplemental insurances to cover dental and other medical procedures (Canada) |

Canada, United Kingdom, (Medicare, USA) |

|

|

Universal |

A single payer (government) provides public insurance. Private insurers also exist to cover special care and are regulated by the government. |

The entire population has access to primary health care.

There is accountability between private and public sectors. |

There is disparity in quality of care between public and private hospitals

Long wait times for special surgeries |

Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Portugal, Turkey |

|

Individuals purchase their own healthcare insurance. |

More control over which doctor you want treatment from

Shorter wait times

Improved facilities |

Individually costly

Creates inequality |

United States |

|

|

Non- universal |

There is a mix of public and private insurance, but there is a set of qualifiers, whether it’s employment, veteran status or some other qualifier. This leaves a population of a country uninsured. |

Able to give care to a population |

Very difficult access to care for the uninsured due to high cost

Quality of care varies widely. |

Bangladesh, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria |

How much does the US pay in healthcare compared to everyone else?

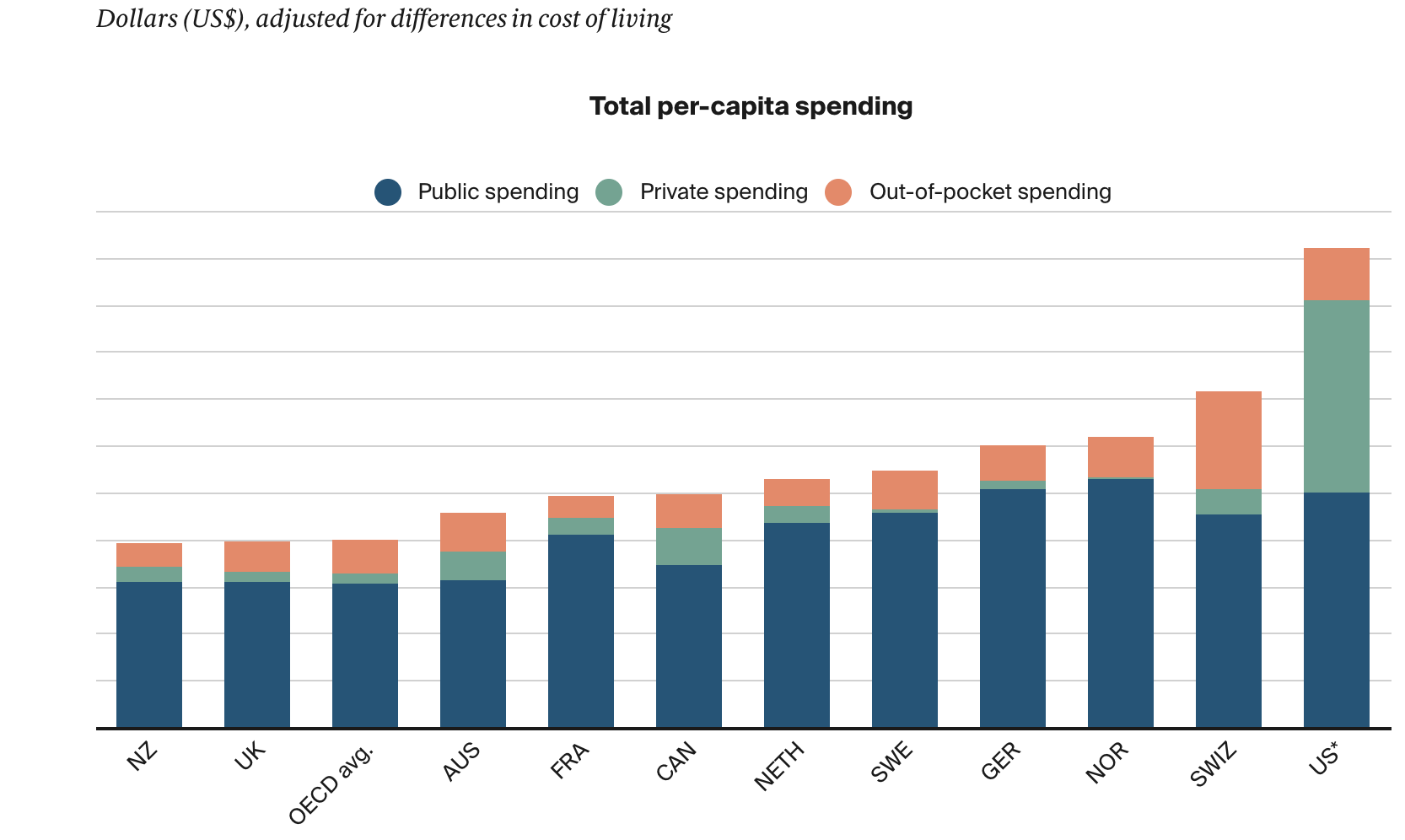

The United States has the highest spending per capita, nearly twice as much compared to other similar high income nations. In addition, the U.S. has the highest per capita private spending of all developed nations, accounting for up to 40% of total per capita healthcare spending (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Differences in Public, Private, and Out-of-Pocket per capita spending(in U.S. Dollars) between the United States and peer countries for 2018 (or the most recent year of published data). Each line of the bar graph represents 1000 USD.

What are we spending money on in healthcare?

Spending in healthcare can be allocated towards the areas listed below:

|

Spending Type |

Description |

|

Inpatient/Outpatient |

Medical services that do (inpatient) or do not (outpatient) require admission into a hospital. Examples include surgeries, rehabilitation, and weight loss programs. |

|

Prescription Drugs/Medical Goods |

Consists of prescription drugs (over-the-counter and clinically administered drugs) and medical equipment (wheelchairs, walkers, etc.). |

|

Administrative |

Services related to the expenses of the organization, its billing practices, and insurance related costs. Examples include legal services, occupancy costs, and wages. |

|

Long-Term |

Any service designed for people with chronic illnesses or disabilities who need assistance or additional care. Examples include senior transportation services, companion services, or medical alert services. |

|

Preventative |

Consists of measures taken to prevent disease. Examples include screenings, counseling, or blood tests to detect and prevent disease.

|

|

Other |

Includes healthcare services carried out by providers in a non-traditional setting. Examples include schools, community centers, and the workplace. |

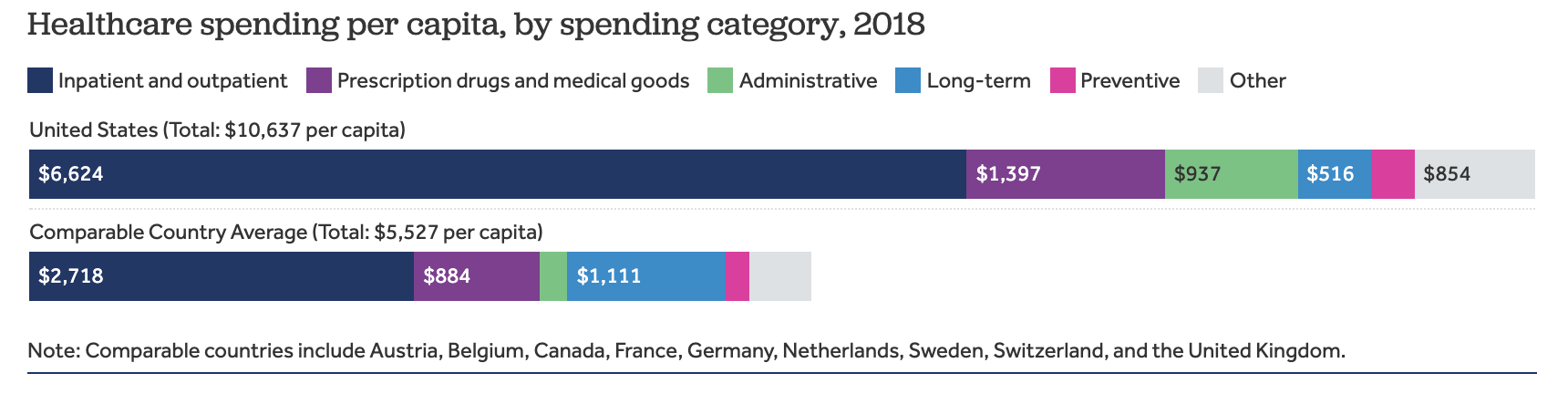

Comparing between the United States and other comparable nations, the main differences in healthcare spending are inpatient and outpatient procedures, prescription drugs, and administrative costs (Figure 2). Increased spending in these areas can be attributed to the type of healthcare systems described above.

Figure 2. Distribution of Healthcare spending in 2018 in the US versus comparable countries. Data taken from the OECD database and analyzed by the Peterson-KFF health system tracker.

To explore more of the data and findings visit the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker and The Commonwealth Fund.

What can be done to reduce healthcare spending?

What can be done to save money in healthcare? The CDC notes that 90% of the United States’ annual health care expenditure is allocated to treating chronic and mental health conditions associated with higher emergency room and urgent care visits. This finding emphasizes the importance that preventative medicine could have in reducing healthcare costs. Preventative medicine focuses on reducing the incidence of chronic disease through regular access to care services such as immunizations, screenings, and doctor visits. A study carried out in 2016 (Musich et al.) found that participants with physicians focused on preventative care had improved health management and experienced decreased health expenditure costs over time.

To learn more about the healthcare costs of chronic diseases and how preventative healthcare reduces spending, check out the CDC and this study.

Who has access to healthcare?

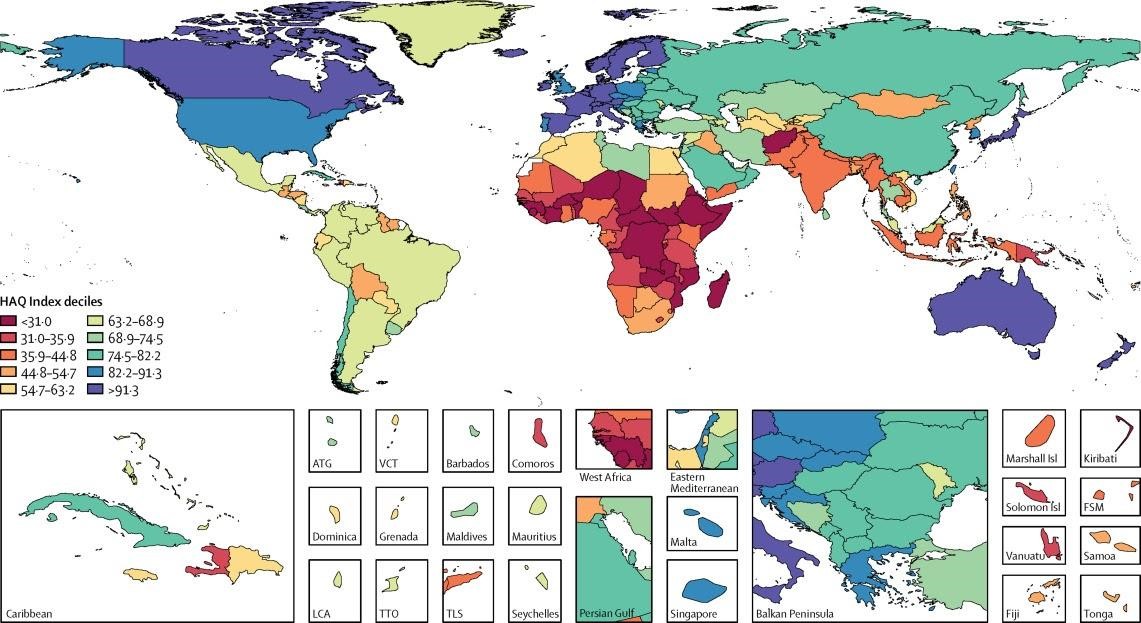

The Lancet collected and analyzed data from a comprehensive global study, “A Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study”, in 2016, comparing healthcare access and quality between 195 countries using the Healthcare Access and Quality (HAQ) Index. The HAQ Index contributes to the evaluation of a particular healthcare system by measuring preventable deaths. HAQ Indexes are graded from 0 to 100, with 0 having the worst access/quality of care and 100 have the highest access/quality of care.

Figure 3. Comparison of healthcare access and quality between 195 countries.

The findings revealed that access and quality of healthcare heavily depends on geographical location. Countries who had the highest scores were concentrated in Europe and countries with the lowest scores were concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. While the United States’ score compares favorably against the rest of the world, comparing against similar high income economies mentioned before is a different matter: the United States lags behind other developed nations, despite paying the most for healthcare.

The world has seen many pandemics, but how ready were we for COVID-19?

In 2019, The Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU) and The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) published a comprehensive report that ranked 195 countries on a Global Health Security Index (GHSI). The report emphasized that no country is fully prepared; in fact 116 countries scored below 50 out of 100. Thailand was the only middle-income country with a score of 73.2, ranking 6th after the US, UK, Netherlands, Australia and Canada. The report concluded that Thailand ranks high because not only does it have a top tier health care system/access monitoring and mitigating infectious diseases, but also has a robust epidemiological training program, national laboratory system and electronic reporting capabilities that are well connected.

How did the pandemic affect healthcare systems?

Although the US has ranked 1st on the GHSI list with an Index score of 83.5, we didn’t utilize the resources that were readily available to us when COVID-19 began spreading across the nation. Through March,the US was close to 30 million cases and 545 thousand deaths. In fact, due to COVID-19, the US life expectancy has dropped one full year, 78.8 to 77.8. This decline is even more drastic when it comes to Black and Hispanic males. According to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the life expectancy of black males has dropped by 3 years and black females by 2.3 years. Hispanic male life expectancy has dropped 2.4 years and Hispanic female by 1.1 years, whereas life expectancy of white males has a decline of 0.8 years and white females of 0.7 years. These drops in life expectancy show drastic differences between who has access to health care and which demographics have been more affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people lost their jobs due to the pandemic, causing them to lose their health insurance, and many more opted out of routine healthcare check-ups that could have saved lives. This is especially apparent in the US because we have an employer based healthcare system. According to the Congressional Research Service report (Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic: In Brief), the overall unemployment rate hit 14.8% in April 2020; among Hispanic workers the rate was 18.9%.

Health care services have been disrupted and halted because of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout the world. The WHO published a report on the impact of COVID-19 on 25 essential healthcare services. The report pointed out that resources were overwhelmed and interrupted, and there was a need for strategic adaptations to keep essential healthcare services running. According to the report, 90% of countries reported disruptions to essential health services due to the pandemic. Routine immunization services were disrupted in 70% of the countries reported and cancer diagnosis and treatment was disrupted in 55%.

Ghosts of previous pandemics, what can we learn from it.

The COVID-19 pandemic tested the strength of many countries’ healthcare systems and showed us where the gaps are to be filled. In some countries, the healthcare systems needed to be disrupted for enhanced and organized pandemic/epidemic response. This was the case in several countries that encountered SARS, MERS and Ebola epidemics. An article published in the British Medical Journal highlighted how the previous pandemic/epidemic experience required some countries to make changes in their healthcare systems to better mitigate future pandemics, and when COVID-19 happened these countries had the measures in place to fight it. For instance, after the SARS epidemic, Hong Kong invested heavily in preparedness, strengthened the link between scientific and policy making communities and consolidated health protection agencies under one umbrella. After Liberia faced the Ebola outbreak, it employed a resilient primary healthcare system that supported surveillance and diagnostic therapeutics. In addition, the country implemented ways for healthcare workers to build relationships with the community to inform the public about misinformation and speak to vaccine hesitancy. Another example is Saudi Arabia, which reformed its healthcare system after the MERS outbreak. Saudi Arabia has implemented an innovative triaging and screening process that included a drive through screening with a 60-second questionnaire. Additionally, the country started a multi-dimensional research program for MERS that resulted in MERS vaccine development in collaboration with Oxford University. Measures taken after the previous pandemic helped these countries better mitigate COVID-19. One change that is common among these countries is the transformation of their healthcare systems to enable a more centralized response, with improved collaboration between the healthcare/science community and policy makers.

Where in the world is the vaccine?

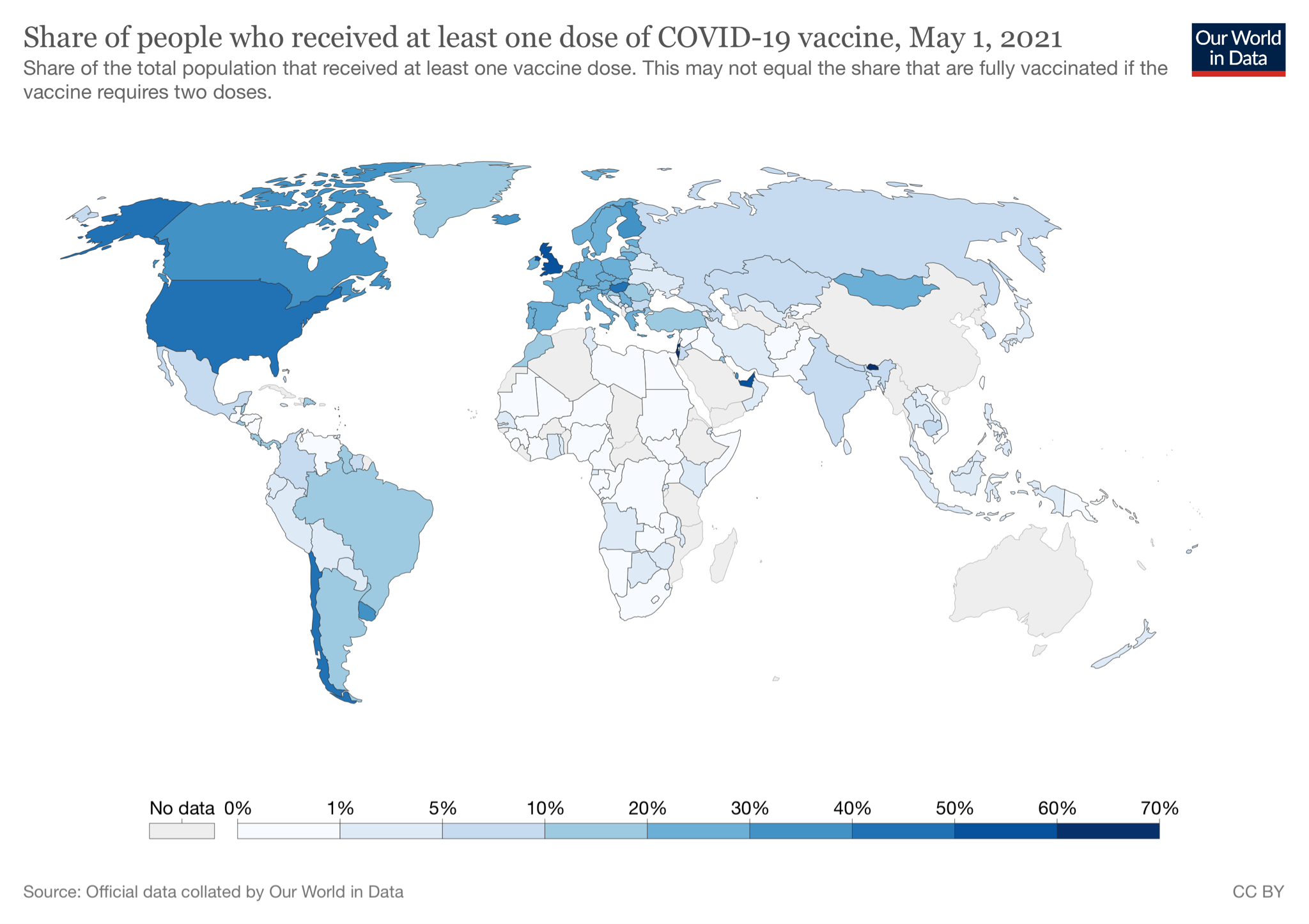

With the toll the pandemic has put on economic, mental and physical health, education, and many other important aspects of everyday life it would be understandable to think that vaccines would be flowing like water all over the world. Unfortunately, this is far from true. The distribution of the various vaccines is highly dependent on a government’s ability to negotiate a contract with a vaccine manufacturer within its budget. As shown by the heatmap below, vaccine distribution correlates with the general wealth of a country. High income countries secured surplus doses during vaccine development or shortly after approval. For example the United States has purchased enough vaccines to cover 1.490 billion extra people--533% of our population. These doses have the potential to be reallocated to less wealthy countries in an effort to spread the health. This is happening in real time as the COVID-19 situation spirals out of control in India and the US prepares to allocate our unused doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine to the country. However, there could be complicating steps during the importing process that could delay the donated vaccines from reaching people in adequate time. For heatmaps, tables, interactive graphs, and downloadable up-to-date information on covid we used Our World in Data.

For reference on the differences between the vaccine distribution and costs here is a snapshot of some of the prices by company for each country from UNICEF (their site has a complete interactive chart too!). Note that Sputnik V, CoronaVac, Covishield and other approved vaccines are not listed here.

For reference on the differences between the vaccine distribution and costs here is a snapshot of some of the prices by company for each country from UNICEF (their site has a complete interactive chart too!). Note that Sputnik V, CoronaVac, Covishield and other approved vaccines are not listed here.

|

|

Pfizer ($) |

Moderna ($) |

astrazeneca ($) |

Janssen ($) |

Sanofi/GSK |

|

African Union |

7 |

|

3 |

10 |

|

|

South Africa |

10 |

|

5 |

|

|

|

Philippines |

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

United States |

19.5 |

15 |

4 |

10 |

10.5 |

|

India |

|

|

2-3 (private market 6-8) |

|

|

|

European commission |

14.70 - 18.90 |

18 |

2.19 - 3.50 |

8.5 |

9.3 |

In recognition of this inequality the WHO has developed the COVAX program to help less wealthy countries obtain vaccines. The program has a three phase distribution plan based on vulnerability and exposure to SARS-CoV-2. The ability for the COVAX program to work is highly dependent on charitable donations from wealthier countries. After a harrowing year of lockdowns and loss we sincerely hope that leaders around the world will work together to put an end to this pandemic.

Possible ways to look at healthcare after this pandemic

As progress is being made in vaccine distribution and we inch closer to the end of the pandemic, we need to collectively think about how we can improve the systems that caused so much suffering during the pandemic. It has been laid out here and many other sources that healthcare systems that prioritize profit create increased cost for the average person and increased discrimination to marginalized communites. Instead of thinking of how to defend these systems, why not question the underlying motives of “for profit” healthcare and propose different methods of distributing healthcare? As this blog has laid out, there are alternative methods of healthcare that do not center profit. While these various methods have their own advantages and disadvantages, what cannot be denied is that these other methods, particularly the national and universal systems, have lower cost and greater access to care on average. If the United States is going to improve its health care system in the long term, we suggest looking at these alternative systems and use them as inspiration to improve our own healthcare system.

SHARE