by Buck Institute

August 14, 2024 . BLOG

At the Buck, Oncology + Neurobiology = Nephrology?

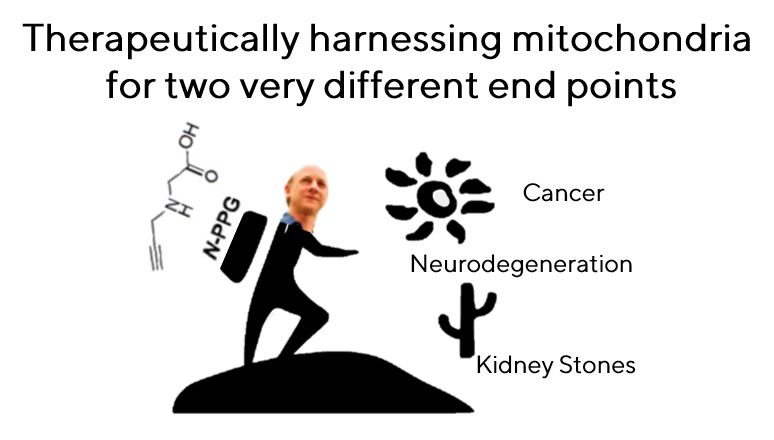

Serendipitous findings lead from a search for anti-cancer agents to a promising treatment for Huntington’s disease … and kidney stones

What happens when an oncologist and a neurobiologist meet in a hallway sounds like it might be the beginning of a bad joke, but it’s actually a story of what new discoveries can be made when differing areas of expertise are combined.

A quest that began as a targeted search for a new chemotherapeutic has led to uncovering how it could be used to reduce the symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases. And in a punchline no one saw coming, the drug turns out to be a very promising treatment for kidney stones.

Dr. Gary Scott

“Our whole story started with a chance encounter with Lisa,” says Gary Scott, PhD, a senior scientist in the Benz lab, referring to Buck Professor Lisa Ellerby, PhD. The Benz lab and Ellerby lab shared space a few years ago, and Scott was chatting with Ellerby about a mitochondrial enzyme (specifically, proline dehydrogenase or PRODH, which breaks down the amino acid proline) that he had been studying.

Scott had been trying to develop a new anti-mitochondrial cancer agent targeting PRODH, evaluating a novel small molecule inhibitor called N-propargylglycine (or N-PPG), which looked promising based on a previous Benz lab publication. When he tested it on cultured cell lines as well as against a mouse tumor model, N-PPG showed some unique and potentially beneficial effects on normal cells.

When he was discussing the results with Ellerby, Scott mentioned that the enzyme caused a biological response known as “mitohormesis.” In this beneficial process, a small amount of stress in the mitochondria of a cell improves the cell’s functioning.

Dr. Lisa Ellerby

“When he told me about observing mitohormesis, I thought it was just a perfect match,” Ellerby says, since her lab had already been thinking about how mitohormesis impacts neurological diseases. “I thought: ‘let's throw your compound on my cells in my Huntington’s disease project and see what happens.’”

What happened in cells wasn’t exactly what they expected, so they decided to try it in a mouse model of severe, rapidly progressing Huntington's disease. This neurological disorder causes movement, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms, and currently there are no treatments for it aside from symptom reduction.

The team showed that N-PPG could cross the blood-brain barrier, which is always critical for a neurological therapy. As they had observed in earlier studies, there were no discernable toxic side effects, and the drug increased mitohormesis, as they suspected. But what was fascinating, says Ellerby, was that the drug corrected the genetic changes (the transcriptomics) that accompany the disease, by about 50%.

“We were kind of shocked, like we just gave this drug to the mouse and it was putting the Huntington’s disease brain transcriptomics back toward normal,” she says. “I don’t think we have ever seen a drug that reversed it by that much.”

“We were kind of shocked, like we just gave this drug to the mouse and it was putting the Huntington’s disease brain transcriptomics back toward normal,” she says. “I don’t think we have ever seen a drug that reversed it by that much.”

Dr. Chris Benz

“The model we chose was a very difficult one; it is the most aggressive model of Huntington’s disease we have,” says Buck Professor Chris Benz, MD. “It is really hard to get something to reverse a pathology when it has already become well established and causing symptoms,” but that is exactly what they saw.

Further analysis of what was occurring metabolically gave the team even more to think about. They discovered that N-PPG was involved with the liver metabolic pathway that produces oxalate, and oxalate is the undesirable end product that produces kidney stones. A new direction of research was born for the team.

“We became quite excited about that, generating our interest in a completely different field: nephrology,” says Scott.

Ellerby was also thrilled about the new direction, as she works on rare “orphan” neurological diseases that affect only a small number of people. She acquired the mouse model for a rare kidney disease that causes rampant kidney stone formation, treated the mice with N-PPG and saw that drug completely cleared the stones along with dramatically reduced oxalate levels.

“We published a paper about this and even used the word ‘serendipity’” says Scott.

“This is not a project I ever would have considered undertaking. I am an oncologist and my lab generally works in the field of cancer and aging, says Benz. “I didn't envision that it would go in the direction of neurodegeneration and kidney stones but that’s where the data and excitement led us.”

“It has been a fun collaboration, and it shows what can happen when your next-door neighbor is open and receptive the way Lisa is,” says Scott.

“It really attests to a unique quality among the Buck Institute scientists: collaborative and interdisciplinary research, not typically found within larger US academic universities and institutes, says Benz.

SHARE